This application note examines durability testing of diamond-like carbon (DLC) and DLC-type optical coatings, with emphasis on what durability means in practice, how it is evaluated, and where limitations remain, particularly when coatings are applied to polymer optical substrates.

It is intended for optical, materials, and systems engineers evaluating DLC coatings for abrasion resistance, environmental robustness, and long-term performance in optical systems.

This document avoids implying indestructibility or universal suitability and focuses on measurable durability under defined conditions.

What DLC coatings are (engineering definition)

Diamond-like carbon coatings are amorphous carbon-based thin films that may include varying ratios of:

sp² and sp³ carbon bonding

Hydrogen (a-C:H)

Dopants (application-dependent)

DLC coatings are used to improve:

Surface hardness

Abrasion resistance

Chemical resistance

Scratch resistance

They are not diamond, and their properties vary significantly depending on composition and deposition process.

Why durability testing is critical

DLC coatings are often selected because of perceived robustness, but durability is not intrinsic — it must be demonstrated.

Durability testing is required to:

Quantify abrasion resistance

Assess adhesion to the substrate

Evaluate environmental stability

Identify failure modes under realistic use

Without testing, durability claims are assumptions, not engineering facts.

Polymer substrates and DLC coatings

Applying DLC coatings to polymer optics introduces additional challenges compared to glass or metal substrates:

Lower allowable deposition temperatures

Large mismatch in elastic modulus

Higher coefficient of thermal expansion (CTE)

Substrate compliance under load

As a result:

Coating stress becomes a dominant design variable

Adhesion strategies are critical

Not all DLC formulations are suitable for polymers

Durability results on rigid substrates do not transfer directly to polymer optics.

Common durability tests for DLC optical coatings

Abrasion and scratch resistance

Typical evaluations may include:

Taber abrasion (with defined wheels and loads)

Scratch testing with controlled tip geometry and load

Wipe or rub testing with defined media

Results depend on:

Test method

Load conditions

Counterface material

Substrate compliance

Abrasion resistance must be interpreted relative to use case, not as an absolute ranking.

Adhesion testing

Adhesion is commonly evaluated using:

Tape tests

Progressive load scratch tests

Cross-hatch methods (where applicable)

Adhesion performance depends on:

Surface preparation

Interlayer design

Coating stress

Substrate material

Good hardness without adhesion is a failure mode, not success.

Environmental durability

Environmental testing may include:

Thermal cycling

Humidity exposure

Chemical resistance testing

UV exposure (where relevant)

Polymer substrates may introduce time-dependent behavior that affects long-term coating stability.

Stress and thickness considerations

DLC coatings are typically:

Mechanically stiff

Relatively high stress compared to many oxide coatings

Increasing coating thickness can improve wear resistance but also:

Increases residual stress

Raises risk of cracking or delamination

Increases sensitivity to thermal mismatch

Durability is a balance between hardness and stress, not simply maximizing thickness.

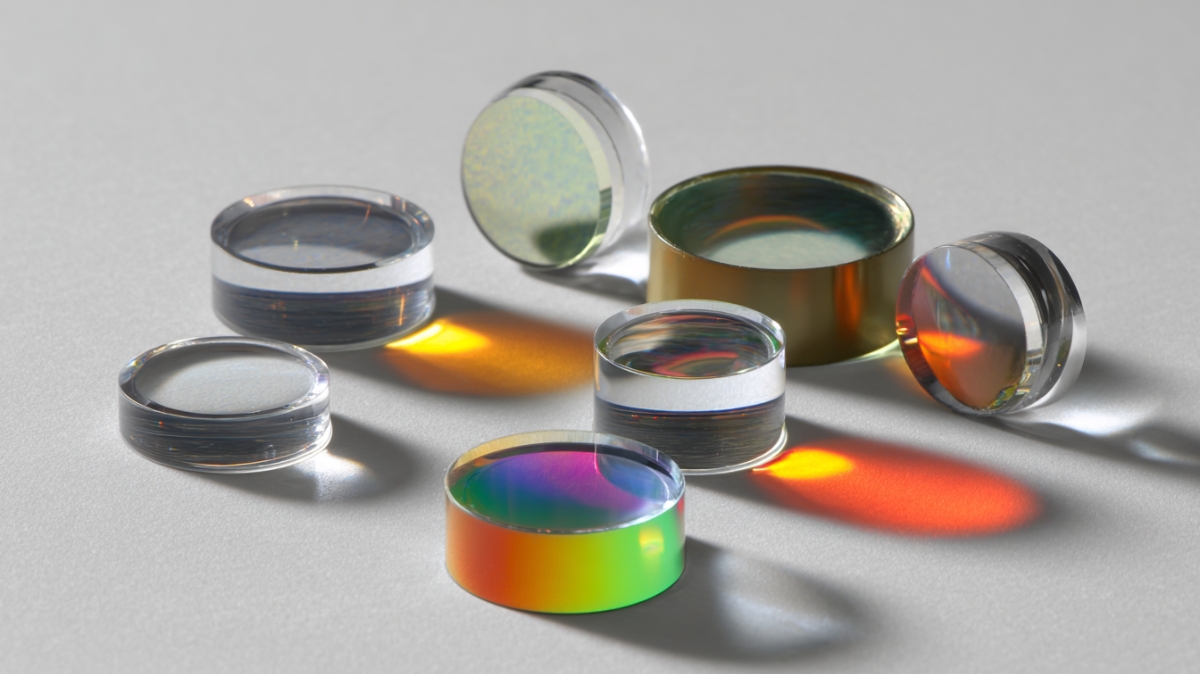

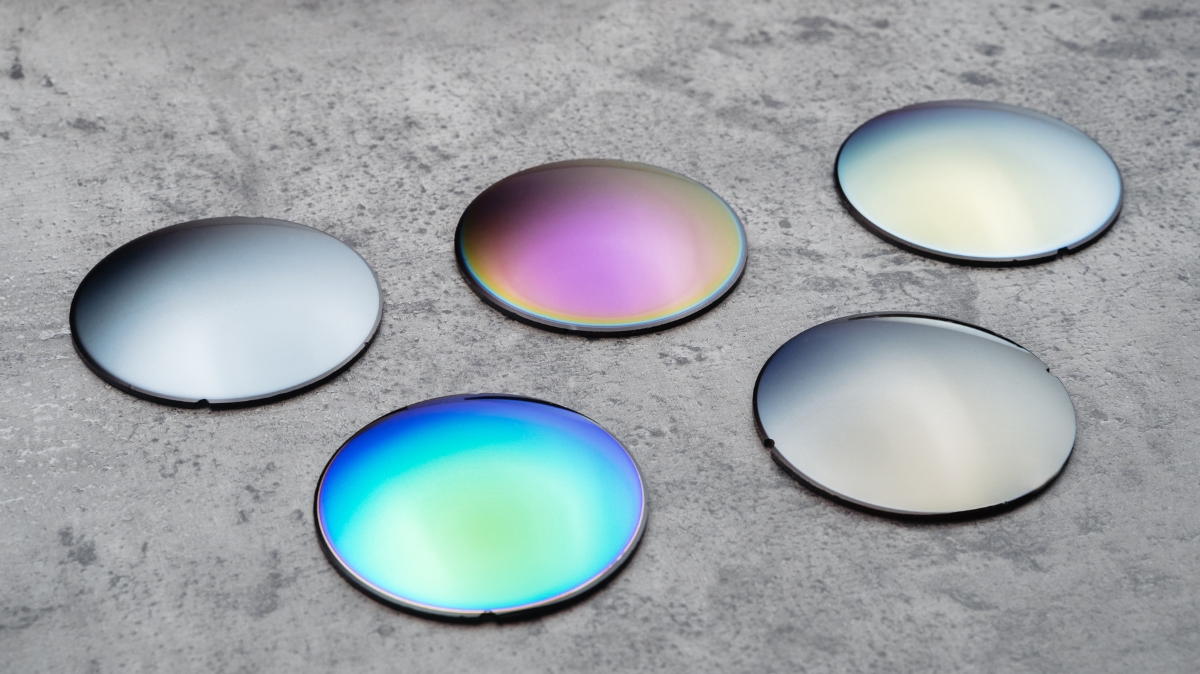

Optical performance trade-offs

DLC coatings can affect:

Transmission

Reflectance

Absorption

Spectral behavior

Optical performance depends on:

Coating composition

Thickness

Wavelength range

In optical systems, durability improvements must be balanced against optical throughput and spectral requirements.

Manufacturing and process considerations

Durable DLC coatings require:

Controlled deposition energy

Stable process parameters

Substrate temperature management

Consistent surface preparation

Process drift can alter:

Stress levels

Adhesion behavior

Optical properties

Durability testing must be tied to qualified process windows, not one-off samples.

Interpreting durability test results

Durability testing should be interpreted with caution:

Passing a test does not guarantee field performance

Failing a test may indicate a mismatch between coating design and test method

Results are only valid for the tested substrate, process, and conditions

Test conditions must be documented and aligned with real operating environments.

Qualification and validation strategy

A defensible DLC durability program should include:

Optical verification

Transmission and reflection before and after testing

Mechanical durability testing

Abrasion and scratch evaluation

Adhesion assessment

Environmental exposure

Thermal cycling

Humidity or chemical exposure (as applicable)

Post-test inspection

Surface integrity

Optical performance drift

Durability claims should be supported by measured degradation thresholds, not pass/fail language alone.

Common misconceptions about DLC coatings

Frequent misunderstandings include:

“DLC is scratch-proof”

“Harder always means more durable”

“If it works on glass, it works on polymers”

“One durability test covers all use cases”

These assumptions lead to field failures, not robust designs.

Summary

DLC coatings can significantly improve surface durability in optical systems when:

Coating stress is controlled

Adhesion is engineered

Optical trade-offs are understood

Performance is validated under realistic conditions

On polymer optics, durability is achievable — but only with substrate-specific design and testing.

Key takeaway for engineers

When specifying DLC coatings for optical durability:

Define what “durability” means for your application

Match tests to real use conditions

Treat stress as a first-order design parameter

Validate performance on the actual substrate

DLC coatings are powerful tools — not magic armor.

Closing the Gap Between Coupon Testing and Real-Part Sign-Off

Apollo Optical Systems supports durability qualification beyond DLC by keeping the work tied to production reality rather than coupon-only confidence:

Translating your threat model handling, cleaning chemistry, humidity/thermal exposure into a durability test plan that reflects how the optic is actually built, fixtured, cleaned, and used.

Planning coating approaches for polymer optics where substrate limits, thermal behavior, and handling steps often determine whether a “durable” stack stays durable in service.

Aligning qualification with verification by defining what should be proven on witness samples versus what must be proven on representative parts, and which pre-/post-optical checks provide release-ready evidence.

Maintaining continuity from prototype evaluation to production repeatability so the coating stack you qualify remains stable as scale builds.

Use the threat-to-test table and sign-off checklist above to draft a one-page qualification brief.

If you want a second set of eyes on whether the plan is measurable and production-representative, especially on polymer optics, Apollo Optical Systems can review the approach before you lock the coating stack.

Conclusion

Durability testing beyond DLC is a qualification problem, not a branding decision. The reliable path is to start with the threats the optic must survive, select tests and severity that reflect real handling, cleaning chemistry, and environmental exposure, and define acceptance criteria that catch optical drift as well as visible damage.

When the plan is substrate-aware, especially for polymer optics, and the pass/fail metrics are measurable in the production test flow, durability becomes a controlled sign-off decision rather than a problem discovered after integration.

FAQs

What tests are used to verify optical coating durability?

Durability qualification typically evaluates abrasion/handling damage, adhesion integrity, humidity exposure, thermal cycling response, and chemical resistance. The right combination depends on how the optic is handled, cleaned, and exposed in service.

Should durability testing be done on witness samples or real optical parts?

Witness samples are useful for early screening and process monitoring. For sign-off, many programs require representative parts or builds because substrate behavior, edges, surface finish, and packaging stress can change outcomes.

How do you choose abrasion test severity for optical coatings?

Severity should be tied to real contact conditions: wipe material, expected cycle count, particulate presence, contact pressure, and cleaning method. Over-severe testing can reject viable stacks; under-testing shifts risk into the field.

What should be measured before and after durability testing?

Record the optical performance tied to system requirements (often spectral transmission/reflectance) and document cosmetic defects consistently. If haze or scatter affects performance, include a repeatable haze/scatter evaluation before and after exposure.

Why do coatings fail after humidity or thermal cycling?

Moisture and temperature swings can expose adhesion weaknesses and increase thermo-mechanical stress, especially when coating and substrate expansion differ. Failures may show up as delamination, micro-cracking, haze, or performance drift.