Phase Fresnel lenses and diffractive optical elements (DOEs) are often discussed as if they’re interchangeable.

They’re not.

They solve different problems, fail in different ways, and place very different demands on manufacturing and system design. Confusing the two usually leads to mismatched expectations — especially around efficiency, wavelength behavior, and tolerances.

This comparison exists to answer a simple question engineers actually ask:

Which one makes sense for my system, given how it will really be built and used?

What a phase Fresnel lens actually is

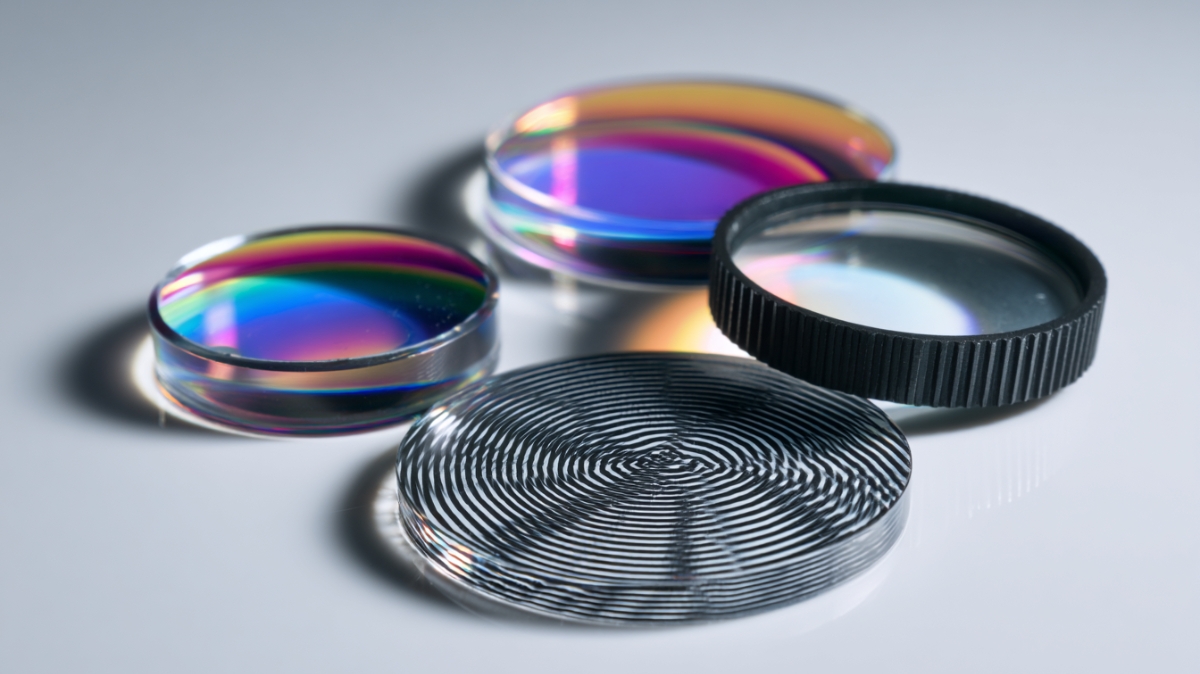

A phase Fresnel lens is a refractive lens approximation implemented using concentric phase steps instead of a continuous surface.

Its goal is straightforward:

replicate the optical power of a conventional lens

with much less thickness and mass

Key characteristics:

operates primarily through refraction

has a defined focal length

behaves predictably over a limited wavelength range

still introduces Fresnel-related artifacts

It is best thought of as a thin refractive lens with compromises, not a diffractive pattern.

What a diffractive optical element actually is

A DOE is a phase-structured surface designed to shape light intentionally through diffraction.

Rather than approximating a traditional lens, a DOE is often designed to:

split beams

reshape intensity distributions

correct specific aberrations

perform multiple optical functions at once

Key characteristics:

inherently wavelength-dependent

strongly sensitive to feature geometry

performance tied directly to fabrication accuracy

behavior is defined by interference, not refraction

A DOE is not a thinner lens.

It’s a patterned wavefront manipulator.

Where people get this wrong

The most common mistake is assuming:

“Both are diffractive, so the differences are minor.”

They aren’t.

A phase Fresnel lens is usually chosen to replace a refractive element.

A DOE is chosen to do something refractive optics can’t easily do at all.

That distinction matters.

Optical behavior in real systems

Wavelength sensitivity

Phase Fresnel lenses are relatively tolerant across narrow wavelength bands

DOEs are explicitly wavelength-dependent and often optimized for a single wavelength or narrow band

If your source wavelength drifts or broadens, DOEs will show it immediately.

Efficiency

Phase Fresnel lenses typically offer higher usable efficiency for simple focusing

DOEs trade efficiency for functionality

High diffraction efficiency is achievable with DOEs, but only under tightly controlled conditions.

Stray light and artifacts

Phase Fresnel lenses introduce groove-edge scatter and ghosting

DOEs introduce diffraction orders and unwanted energy redistribution

Neither is artifact-free — they just fail differently.

Manufacturing reality (where decisions get made)

Feature scale

Phase Fresnel features are typically larger and more forgiving

DOE features can be extremely fine and unforgiving

This directly impacts:

tooling complexity

replication yield

sensitivity to process drift

Tolerance sensitivity

Phase Fresnel performance degrades gradually

DOE performance can degrade abruptly

A small dimensional error that barely matters for a Fresnel lens can completely change how a DOE behaves.

Polymer optics considerations

Both elements can be made in polymers, but the risks differ.

With polymers:

thermal expansion matters

long-term dimensional stability matters

replication fidelity matters

DOEs tend to be less forgiving of polymer behavior over time, especially in environments with temperature cycling or humidity exposure.

Phase Fresnel lenses generally tolerate polymer variability better — but still require validation.

When a phase Fresnel lens makes sense

Phase Fresnel lenses are usually the better choice when:

you need a thin focusing element

wavelength range is known and limited

efficiency matters more than complex beam shaping

manufacturing robustness is important

the optic must behave predictably over time

They are often selected for practical systems, not experimental ones.

When a DOE makes sense

DOEs are the right tool when:

the optical function cannot be achieved with refractive optics

beam shaping or splitting is required

system complexity must be reduced

wavelength and angle conditions are tightly controlled

the application tolerates sensitivity and complexity

They shine in purpose-built systems, not general ones.

Comparison summary

Primary function: Phase Fresnel Lens (Thin focusing), Diffractive Optical Element (Wavefront shaping)

Wavelength sensitivity: Phase Fresnel Lens (Moderate), Diffractive Optical Element (High)

Efficiency: Phase Fresnel Lens (Higher for simple optics), Diffractive Optical Element (Function-dependent)

Manufacturing tolerance: Phase Fresnel Lens (More forgiving), Diffractive Optical Element (Highly sensitive)

Polymer suitability: Phase Fresnel Lens (Better), Diffractive Optical Element (More constrained)

Failure mode: Phase Fresnel Lens (Gradual degradation), Diffractive Optical Element (Abrupt behavior change)

The real decision driver

The right question is not:

“Which is better?”

It’s:

“Which one fails in a way my system can tolerate?”

That’s the engineering truth behind this comparison.

Bottom line

Phase Fresnel lenses and diffractive optical elements are not substitutes for each other.

They represent different philosophies of optical design:

one prioritizes predictable behavior

the other prioritizes functional flexibility

Choosing correctly requires understanding:

how the optic will be made

how it will be used

how it will age

and what happens when it’s no longer ideal

That’s where real systems succeed or fail.

How Apollo Supports The “Buildable And Provable” Version Of The Design

Once you’re past definitions and into pass/fail requirements, the work shifts from “can it work” to “can we build it consistently and prove it every time.”

Apollo supports that transition by:

Converting optical requirements (wavelength/bandwidth, MTF/contrast or uniformity targets, stray light limits) into a manufacturable architecture phase Fresnel/DOE, refractive Fresnel, or hybrid using DFM-style review and tolerance thinking.

Keeping prototypes production-honest so early validation reflects the realities of volume builds, not a one-off lab success.

Building verification into the plan early, what gets measured on the optic versus in the assembled system, and what pass/fail looks like in the conditions you actually operate in.

Advising on optical-grade polymer selection based on environment, cleaning/handling exposure, and durability requirements that can shift performance over time.

At this stage, what matters most is repeatability and proof: ISO 13485 alignment for regulated programs, in-house optical metrology/testing, and an end-to-end workflow under one roof (design → build → coat/assemble → verify) that reduces handoffs and variability.

If you’re weighing phase Fresnel/DOE versus refractive or hybrid options, talk with Apollo about a short architecture-and-verification review to confirm what’s buildable, measurable, and scalable before you lock the design.

Conclusion

Phase Fresnel and diffractive optics aren’t competing labels; they’re often the same conversation at different levels. The real decision is whether a phase-based approach helps your system hit its target without introducing bandwidth sensitivity, stray light behavior, or verification gaps you can’t control once you leave the bench.

If you take one thing from this comparison, let it be this: don’t lock an architecture on thickness or novelty. Lock it on the metric your product is judged on: MTF/contrast, uniformity/pattern accuracy, or sensing contrast, and make sure the design is manufacturable and measurable in the final package. That’s where many “good designs” quietly fail.

When the requirements are clear and the verification plan is real, the choice between refractive Fresnel, phase Fresnel/DOE, or a hybrid stops being philosophical. It becomes a controlled engineering decision you can scale.

FAQs

Is a phase Fresnel lens the same as a diffractive optical element (DOE)?

In most engineering usage, a phase Fresnel lens is a type of diffractive optic (i.e., it sits within the DOE family). The confusion comes from people comparing a specific DOE subtype to the broader category.

What’s the difference between a Fresnel lens and a Fresnel zone plate?

A “Fresnel lens” in products is usually refractive (a conventional lens collapsed into steps), while a Fresnel zone plate focuses primarily through diffraction/interference. They look similar (rings), but behave differently.

Why are diffractive optics more sensitive to wavelength and bandwidth?

Diffractive optics work by shaping the phase and rely on interference effects, so performance often shifts more noticeably with wavelength than purely refractive designs. That’s why you need the operating band and bandwidth defined early.

Do diffractive/phase Fresnel elements increase stray light or ghosting?

They can, depending on design details and how energy distributes into different behaviors (e.g., artifacts/structure and scatter). Treat stray light as a requirement with a test method, not as something to “tune out” later.

Can diffractive optics be made thin and lightweight compared with refractive optics?

Often yes—thin, compact form factors are a common reason teams use diffractive optics, especially in micro-optics contexts. The practical constraint is whether performance remains stable under real system variation.